Ash Wednesday

This Lent I will turn atheism to ashes[1]

Around 4:30 today as daylight dimmed, Bobby and I burned the palms from last Palm Sunday in the churchyard to make the ash we’re using tonight. After the Litany of Penitence, we’ll trace a cross of ashes on your forehead with these words from the third chapter of Genesis, the very beginning of humanity’s long story of life with God: for dust you are, and to dust you will return.

The Hebrew Bible tells countless stories of God’s people using ashes to express grief or repentance. Jonah warned the people of Nineva to repent by fasting and wearing sackcloth and ashes so that God would spare them. Job repented in dust and ashes. Jeremiah calls for repentance by saying: O daughter of my people, gird on sackcloth, roll in the ashes. The prophet Daniel turned to the Lord God, pleading in earnest prayer, with fasting, sackcloth, and ashes. The gospels remember sackcloth and ashes as Jewish practices, and early Christians continued to associate ashes with turning our hearts back to God, recorded as far back as the gospels in the first century, and in Tertullian’s writings in the second. From the first century of the Common Era, they sprinkled ashes on their heads and traced ash crosses on their foreheads to mark their intentions of faith.

Now, I’ve been an Episcopalian all my life, and I grew up in the minority in a community of Roman Catholics, so I’m used to these questions: What are you giving up for Lent? What will be your Lenten fast? I’ve heard — and probably asked — these questions many, many times. And — maybe like you — I’ve “given things up” for Lent. I’ve fasted from chocolate, coffee, sweets, and wine. And I wonder whether this was really what Jesus was up to during his 40 days and nights in the wilderness. I wonder if I have grown in discipleship from these disciplines over the Lents of my lifetime, and I wonder if there is a different way to think about it. John the Baptist preached repentance, which in the original Greek of the New Testament would have been the word metanoite — which means a change in the way you see things.

The Latin translation of metanoite is repentance. There are many associated words in English — penalty, punishment, punitive, penal system — and so the use of the word repentance in John the Baptist’s cry in our English translation of the gospels gets all tied up in those associated words. We start to think of repentance as punishment — self-denial, abstinence, and even suffering. We think of repentance as stopping doing bad things rather than seeing and experiencing the world and our relationships in a new way. And sometimes it seems that we need to suffer — or to give things up — for that punishment.

Was Jesus suffering in the wilderness those 40 days and nights? Maybe. Scripture tells us that he was tempted — he wrestled with hard ideas like earthly power, ego, control over his future, and obedience to the life he was choosing. But did he give up chocolate — or more likely in his Ancient Near East context, dates, olive oil, or wine? I’m not sure that was the focal point of Jesus’ experience in the wilderness, even though the gospels said that he fasted. Jesus was working during that time. Jesus was preparing himself for his own earthly ministry, and Lent is the time we prepare for our own earthly ministry — what comes next for us after Easter.

How can we use Lenten fasting to keep our focus on our best intentions of being the people of God we mean to be? I read an essay in The Times by British columnist Giles Coren about his decision to give up atheism for Lent. Coren is part of the growing majority in Western countries that, even if raised to identify as Christian or Jewish, does not attend church or synagogue or hold or practice any faith. The essay is a tender, funny, and accessible description of fasting from skepticism, exercising the discipline, and flexing and strengthening the muscle of faith. I commend the whole essay — called This Lent I will turn atheism to ashes — to your attention.

But the gist of Coren’s writing is the discipline of presence, of simply showing up for the holy, and not getting ourselves all dug in about what we don’t believe, and what we don’t agree with, but committing, and remaining open to discover, what we can commit to, how we do connect, and when we can endorse and affirm. I think it’s really helpful to talk about Lenten disciplines, which expands our thinking beyond fasting — or giving something up — to a practice we take on or commit to keeping. Discipline — you hear the root word there — is also how we become disciples, that is practitioners of our faith. And a huge part of becoming — and discovering to our own surprise that we are — disciples is simply showing up for each other and witnessing each other’s lives, whether triumphs, joys, tragedies, or sorrows.

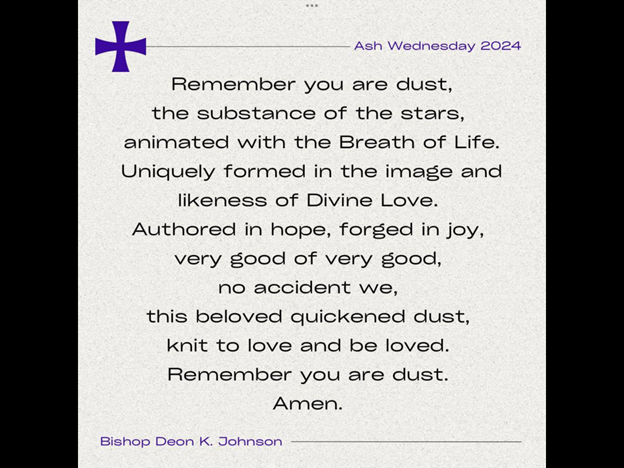

Any time we connect with each other in love and compassion, even through pain and loss, we are fasting from skepticism, exercising discipline, and flexing and strengthening the muscle of faith. Often we, and our past sorrows, are redeemed by these connections and we are made whole again. We get a “do-over” on a traumatic experience or pain that can help us to relate to that event in a new, more positive way, knowing ourselves as disciples — people of kindness, empathy, faith, and connection. The Lenten discipline I do commit to, with all my heart, is to listen with compassion and empathy to your lived experience and context, always ready to learn something new or change my mind. Let’s make it our Lenten discipline to walk together as who we are: one community of many, and together the body of Christ. I believe that this is the fast that God wants. As Bishop Deon K. Johnson, of the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri writes:

[1] Giles Coren, “This Lent I will turn atheism to ashes,” The Times Friday, March 7, 2025.