Pentecost 5

And the Lawyer asks: “who is my neighbor?"

One evening last May, I had dinner with two close friends, whom I met during my seminarian year at St. John’s Church in Stamford. My friend Kathi was senior warden at the time. Her husband, Ron, is the present warden. St John’s is a pre-Revolutionary church, around which the City of Stamford has grown up these past 280 years. It sits in the center of a dense urban community where its ministry is guided by the needs of the less fortunate.

Central to its ministry is the care and feeding of the homeless and unemployed that surround them. Every week, the St. John’s family provides meals for the needy from their large kitchen and dining facilities. Just as we do at Emmanuel, parishioners also volunteer at food kitchens and distribute food packages. Why am I not surprised, then, as my friend Kathi, a career nurse, describes their recently expanded outreach to the swelling immigrant population. Each week, parishioners gather. They prepare sandwiches. They drive to locations, say, on a corner near Home Depot, where immigrants gather, seeking a day’s labor. There they offer sandwiches and refreshment to the laborers. These are usually consumed immediately. This may be the only meal the job seeker will have that day.

It is a profound act of grace. It is an act of hope. It is discipleship in action. As you have done it unto the least of these, my brothers, you have done it unto me. (Matt 25:40)

This morning, in the parable of The Good Samaritan, Luke opens our window to the Kingdom of God. As in each of Jesus’ parables, we enter a strange world where everything seems familiar yet becomes radically different.[i] A world where the destitute are surprised by their good fortune. Where the self-assurance of the powerful is flipped upside down.[ii] Where the assumptions of our daily life are reversed.

Walk with me through the mystery of this ancient story. Seeking meaning for ourselves in this world of ours.

Jesus is on the road to Jerusalem. Preaching and teaching discipleship. Along the way He is challenged by a lawyer. The lawyer tests Jesus with the question: “What must I do to enter the kingdom of God?” Jesus reminds him to check his law school lecture notes on Leviticus. The lawyer does, responds with the correct answer: “I must love my neighbor as myself.” (Lev 19:18) However, the experienced litigator, determined to establish his point, presses on, saying: “but it always depends on what the meaning of the word ‘it’ is, no?” “Who is my neighbor?”

Down the years, the parable of the Good Samaritan has been interpreted by many gifted theologians. Some interpret the traveler as Man’s fall from Eden, as our traveler descends the perilous road from Jerusalem to Jericho, 3,000 feet below. The traveler whom Jesus, now in the person of the Good Samaritan, rescues from his fall from Paradise.[iii] Others interpret the Samaritan as Christ who, in His mercy, comes down from heaven, becomes our neighbor, and heals the wounds of the human race.[iv] Well… perhaps. Kind of tempting to entertain such scholarly insights. But perhaps these thoughtful interpretations distract us from the message of hope that Jesus intends.

In his parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus turns the social code upside down. He flips the social boundaries that support the powerful. The boundaries that separate the clean from unclean. The boundaries that define who qualify to be our neighbors. An unknown traveler is assaulted. Left alone, perhaps to die, in a ditch along the road. A priest and Levite, two respected members of the establishment come near, yet pass by. They shun the gravely wounded traveler. Their religious code prohibits them from approaching the unclean dead or touching the blood of the injured traveler. The wounded, beaten traveler does not qualify for their mercy. The traveler is not their neighbor.

And now a Samaritan approaches. So often we have referred to this man as the “Good” Samaritan. In the eyes of the Jewish community, he was anything but good. The Samaritan is a foreigner who worshiped in a different way, in a different place than the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. It is the Samaritan, one despised and rejected by Jewish society, who binds the wounds of this stranger. In this act of mercy, the Samaritan reveals the bounty of God’s love. For his is an open-ended guarantee. There is no limit on the cost the innkeeper may incur for the traveler’s care.[v] There is no limit on who we shall define as ‘our neighbor.’

The Samaritan calls us to dispense justice and mercy to all persons. Hear God’s ageless call for justice from Amos, the eighth-century Hebrew prophet. Amos condemns the upper class of ancient Israel for exploiting the poor and trampling the needy.[vi] Amos challenges the powerful and privileged who fail to dispense mercy according to Hebrew law, according to the plumb line of the Lord. For failing God’s call to love one’s neighbor as oneself, he prophesies the downfall of the nation of Israel. (Amos 7:17) For Amos, to serve God is to practice justice. He demands justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream. (Amos 5:24)

Now, how shall we respond when the lawyer turns to us and asks: “friend, who is your neighbor?” Never has that question been asked with greater urgency. How do we tear down the barriers that separate us from those who disagree with our worldviews? Those who separate themselves from friends and family over political or religious differences? Who amongst us does not remember the example of Fred Rogers? Mister Rogers leads the way. He invites us: “Won’t you be my neighbor?” In accepting his invitation to enter his Neighborhood we enter a world of kindness, compassion and respect for differences. In his Neighborhood, everyone is special and valued.

In welcoming the stranger, the members of St. John’s - Stamford accept that invitation. Perhaps they see a different identity in the wounded, beaten, bleeding traveler on the road to Jericho. That lonely man in the ditch, rejected and abandoned by the world. The person of Christ crucified. Beaten, rejected by the world, abandoned by all, left to die alone. In showing mercy to the abandoned, unclean traveler, the least of them, the Samaritan does it also unto God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. (Matt 25:40)

And Jesus turns his face to us and says: “Go thou, and do likewise.”

Works Referenced:

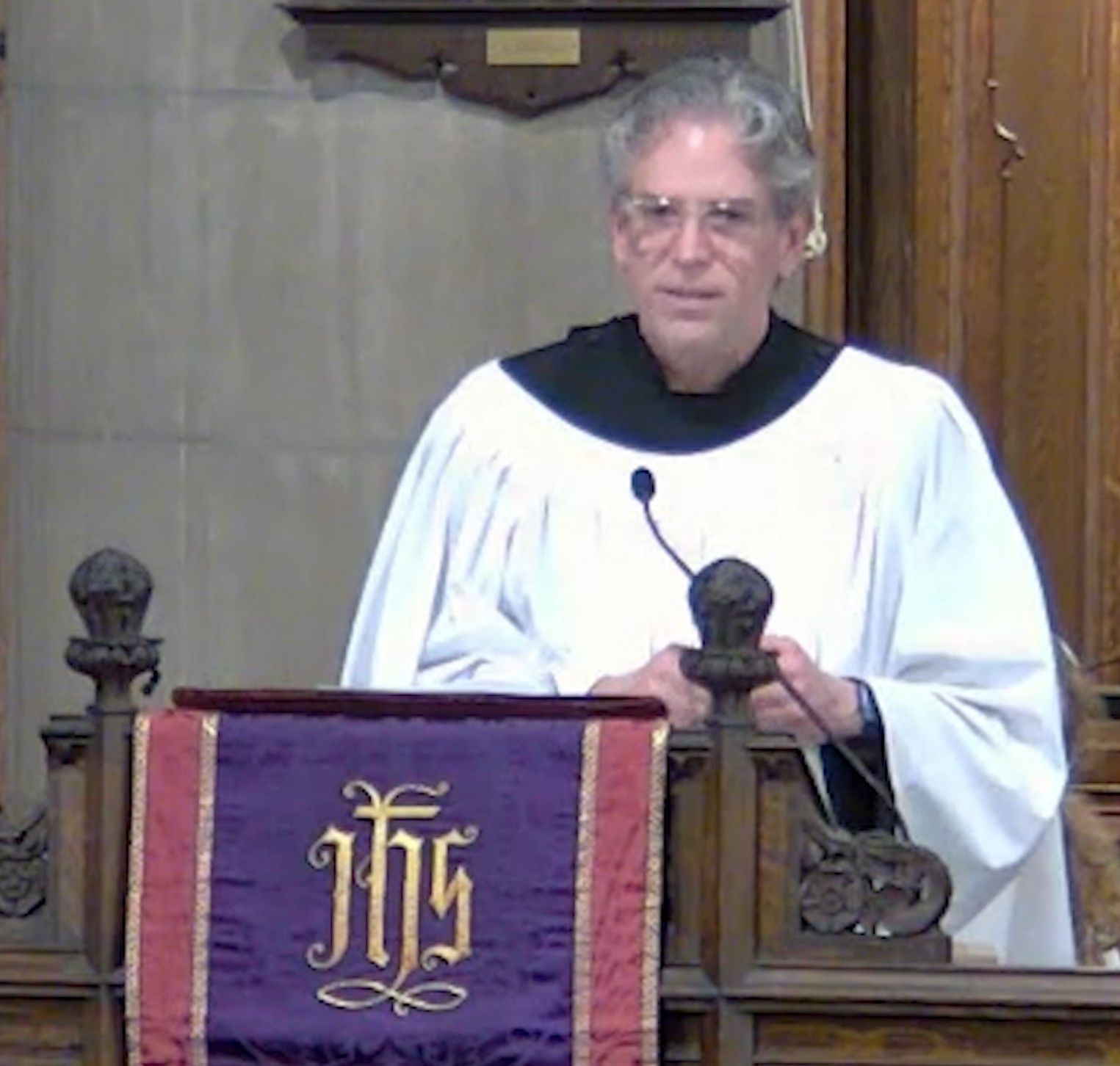

This is a sermon delivered to the congregation of Emmanuel Church, Newport, RI on July 13, 2025. I am indebted to the following for their insights into the lectionary: Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, Eerdmans (1997); Robert W. Funk, The Parable as Metaphor in, Funk on Parables, Polebridge Press (2006)_and, Parables and Presence, Fortress Press (1982); Richard Lischer, Reading the Parables: Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church (2014); John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Fortress Press (2014); and Mark A. Proctor, “Who is my Neighbor?”, Recontextualizing Luke’s Good Samaritan, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol 138, No.1 (2019) pp. 203-219

Roger C. Bullard, MDiv

July 13, 2025

[i] Funk, The Parable as Metaphor, p 51

[ii] Funk, Parables and Presence, p 17-18

[iii] Green, p 429

[iv] Lischer, p 152

[v] Green, p 432

[vi] Collins, p 460-461