Pentecost 6

A Basket of Summer Fruit

We’ve been talking about hope these last weeks — what it takes to build hope, and how we can speak hope into being. We need to have a resilient hope to lift us up, when we, or those we care about, hit hard times. And hope has a snowball effect: the more hope we have, the more hope we need, because that’s just the way hope works. That’s why building community here at Emmanuel is so important: Hope all starts with connection — to God and to each other. Connection and community build relationship. Relationship brings about belonging — a sense of connection and purpose — where you know you’re missed when you’re away. Belonging yields joy. And joy opens the door for hope — that longing for the very best for those we care about — family, friends, our community, and the natural environment. So anyone want to guess where I found hope in today’s scripture?

In a basket of summer fruit. Peaches from Georgia are in season, and I now have a line on a direct supply. I’m buying them by the box, and after a day or two on the counter, they’re perfectly ripe and juicy. I had fantasies at first of making this prize into peach preserves, saving their bright, sunny flavor to cheer our dour English muffins in dark December, or maybe remind us of sunshine in March’s freezing rain. Or possibly I’d make a peach cobbler, or one of those cool New York Times recipes for rolling sweet, juicy peach bits in prosciutto, or serving this summer fruit sliced alongside tomatoes. But my peaches never survive the day. I eat them plain, greedily, and with their brilliant, succulent juices running onto my hands, in the wild abandon of a sticky kid on summer vacation. I’ll remember the peaches’ intense, juicy, summer fruit flavor in December, when the sun begins to set at 4:30, to bring my thoughts back to God’s bounty and grace.

A basket of summer fruit is more than just a snack or a treat or a dessert. It’s a basket of joy that triggers memories of belonging as rich and fresh as the juice running down my arm. Maybe that’s why Amos begins his gloomy prophecy in our reading today with a basket of summer fruit. It’s hard to listen to prophets. They’re depressing, for one thing, always going on about gloom and doom, and the inevitable — they say — consequences of our failure to listen and heed their advice. And their warnings are so dire. Also, if we don’t translate their context into something we understand in our lives, we can lose the thread of what they’re trying to tell us. Take our friend Amos, for example. This is the same Amos of the plumb line from our Old Testament reading last week. Even though it can sound like another time in a far-off, unfamiliar place that doesn’t have any meaning to us today, if you put Amos’s references into our context, his prophecy is, as they say on TV, ripped from the headlines.

So what did Amos really say? He’s calling out the values of a culture and an economy that has gotten distracted from God’s justice and love. Amos is telling us what happens when a society loses its connection with generosity, humanity, and grace and starts racking up points on the wrong scoreboard, and is worried and distracted by many things. Will I have enough? Will we be able to maintain our standard of living? How do we maintain our comfort and convenience with regulations protecting our economy and natural resources? We will make the ephah small and the shekel great, Amos says of those who have lost touch with a sense of belonging and connection to the common good. They practice deceit with false balances, Amos says. Higher prices for less — food, clothing, school supplies, housing — are just one example of a slippery slope — that gradual and often unaware slide from a specific standard into a free fall of mal-adaptation. When we hit the bottom of the slide with a bump, we wonder how we got there and can no longer remember or return to the place where we started, or the person we were.

Is profit wrong? Of course not. That’s not what Amos is saying. Amos is telling us to pay attention — to remember that we’re all in this together, connected through our shared humanity. This is what Amos’s plumb line is for. The plumb line shows us which way is straight when our walls, our standards, and our lives have gone crooked, sometimes in such imperceptible ways over time that we can’t even say when things began to change. With the basket of summer fruit, Amos reminds us of those sweet fruits of the spirit — love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control — that can put us back into right relationship with God and with each other, because it’s that relationship and connection that gives us the hope we need to pull together. We are spiritually and relationally starved without the fruits of the spirit. The famine that Amos is talking about — the consequence of our failure to listen and our resulting stray off plumb — is a famine of the fruits of the spirit. If we don’t keep that basket of summer fruit in mind in the cold, dark days of winter, when our own challenges and struggles overwhelm us, we will no longer hear God’s voice. If we’ve lost all sense of connection — to standards of weights, measures and plumb lines, we will no longer even recognize our own isolation, and we won’t be able to fix it.

It’s the same with Mary and Martha. I love to cook and to share big family meals, and I love to entertain. As a Martha myself, I’ve always bristled at Jesus’ response to Martha’s reasonable — in my view — request for a little help in the kitchen. Mary’s just sitting there, right? And the dinner is not going to cook itself, particularly over fire in the back yard. And yet Jesus tells Martha to stand down. Mary, he says, has chosen the better part, and it will not be taken from her. Ouch. That was always a judgment that hurt, and I couldn’t reconcile it with everything else I knew about Jesus, who, after all, prepared dinner all by himself for 5,000 people on short provisions without breaking a sweat, just the chapter before today’s reading in Luke’s gospel. But Amos shows us that reading Jesus’ words as a dismissal of the value of Martha’s hospitality is at least 10 degrees off plumb, which over the distance of years between their conversation and our reading today is a big misunderstanding. Let’s go back and measure again: With Jesus’ own focus throughout the gospel on table hospitality, eating and drinking with sinners, it just can’t be that he is really saying that sitting still and listening at God’s feet is qualitatively better than — to be ranked and preferred over — the nurturing expression of love that comes of a shared meal, well prepared and lovingly served.

Berkeley at Yale’s Dean Andrew McGowan, an internationally recognized New Testament scholar, noted in his excellent blog this week that Martha is the head of a large household, likely with many cooks and other workers. A women-run household was notable but not unheard of in those times, so this story calls us to pay special attention. Jesus would have realized the scope and complexity of fixing dinner for Jesus and all the disciples and extra guests at Martha’s house. Jesus is telling Martha not to get distracted by details and keep the main thing the main thing: God’s ultimate purpose of bringing us all together around a table, and making sure everyone has enough. God is not against cooking or hosting or any activity that connects us and gives us mutual concern and joy. The only thing God is against in this picture is the worry and distraction that keeps us from belonging, which builds hope.

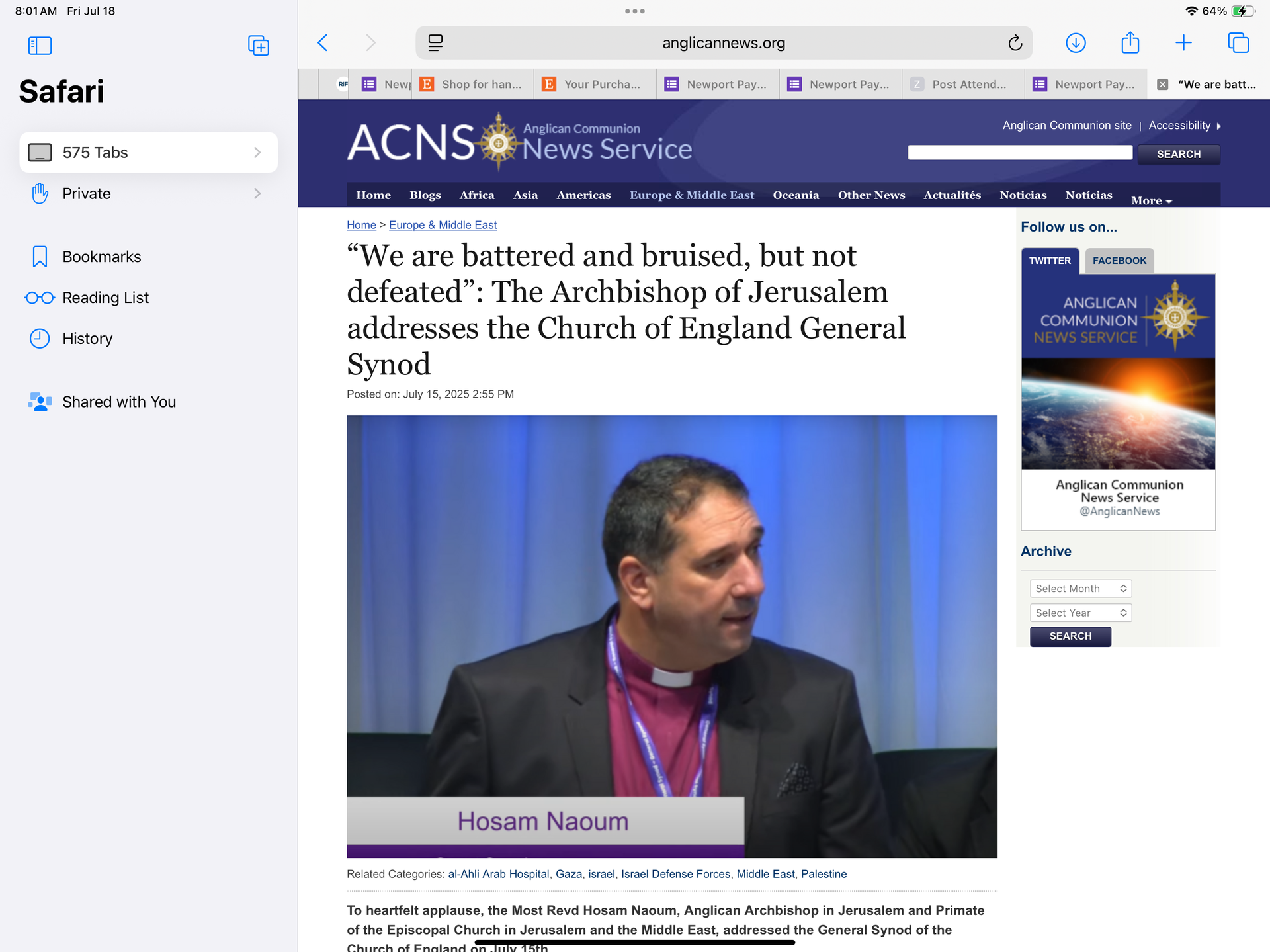

A muscular and resilient hope makes our hearts rush in deep concern wherever our relationships and connections are, and their hearts to rush to ours. I think of Archbishop Hosam Naoum of Jerusalem, Primate of Jerusalem and the Middle East. Hosam — I have to remember always to call him Archbishop Hosam — we worked together during my year in Jerusalem when he was Dean of the Anglican Cathedral there. I always told him that he was my pastor, and his response was always you are my pastor.

We are battered and bruised, but not defeated, Archbishop Hosam said before the Church of England Synod this past week. He’s leading the Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the whole Province through the darkest days imaginable in these times — through the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, with their infrastructure and homes destroyed, tens of thousands killed, and a famine in the land. Through repeated bombings of Al Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, the Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem’s mission, through the killing last week of the most knowledgeable and senior doctor at the hospital on the way home from work at the hospital.

Archbishop Hosam has said repeatedly that their greatest temptation in these times is despair. Their hope is in our hearts that rush to where they suffer. The war puts our family — Christians of all denominations, and Episcopalians specifically, as well as their families, neighbors, and friends who are Muslim, Jewish, Druze, or claim no faith — in existential danger. As Archbishop Hosam reminds us, The Province of the Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East extends into five countries and supports hospitals, clinics, schools, rehabilitation centers, and guest houses in that region. These are our arms of ministry in which we show God’s faith, or our faith in God, through action and ministry of reaching out to those who are disadvantaged, healing the sick and teaching reconciliation with peace and justice, welcoming pilgrims, and offering hope; these are at the heart of our ministry. This is not us and them. This is us and us. May all our hope and prayers and actions be directed to justice and peace. Amen